3 - Funding Innovation for Agriculture: Getting Tactical, Part 1 - The Problem with VC

It turns out that this is NOT a biweekly newsletter. It’s a when-I-have-time-and-thoughts newsletter. Fortunately there’s like, a million agtech newsletters these days, so you’ll be ok.

This week, I’m not writing about key takeaways from World Agritech because that’s covered here and here and elsewhere. I will, however, express my deep gratitude for the many awesome people who work in the wonderful world of agtech that I had the privilege of spending time with this past week. I’m in extreme hustle mode on the roller coaster of building a thing, and getting to spend time with the people who are in the same boat, in the same industry, is energizing and inspiring.

Now, to the content…

There are way fewer animal metaphors, emojis, and AI-generated unicorned-critters today than were in Cows & Chickens 🐔 & Bivalves, Oh My, and there’s a lot more financial jargon.In my opinion, financial jargon is at least as arbitrary up as my animal-company metaphors, and it serves mostly as an exclusionary moat. I tried to minimize use and translate where necessary.

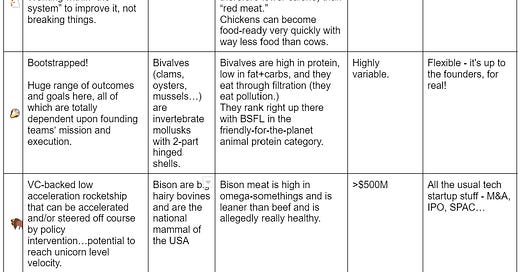

I’ve included an updated version of the animal-company (read last edition if you’re new here) chart, because I’ll be referencing🐔🐄 🦪🦬🦄and 🐉-companies throughout.

You’ll notice that I introduced a new animal - the Dragon. 🐉-companies have been a topic of VC conversation for a while now. Dragons are fund-makers - that is, they are the company within the fund’s entire portfolio that returns >1x the entire fund. If you want to dive deeper, check out this TechCrunch article from 2014.

The Status Quo

Many (most?) venture capitalists are 🦄 hunting. There are two main pieces here that I think are problematic in the context of technical solutions for agriculture.

1 - The “get big or die trying” mentality

This has been largely driven by tech bro/billionaire deification, and it’s problematic for a whole host of societal reasons that I’m not going to get into here. In agtech, specifically, I have seen this play out negatively far more times than I’d like.

Here’s how it happens:

Agtech founder, who we’ll call David*, with good ideas and good intentions raises a couple million from a “normal” (non-ag) VC shop at a nice shiny valuation. “Normal” (non-ag) VC partner, who is a very nice and accomplished white man who we’ll call Michael*, takes a board seat as part of his firm’s investment. David starts to get hints that Michael fundamentally does not understand the market that the company is playing in. At the same time, he gets a ton of value and guidance relating to corporate governance, team building, fundraising, financial reporting - all those weird startup things that most people just don’t know are relevant or important until, suddenly, they are. So, David doesn’t worry too much about Michael’s ag short-falls, because Michael is super helpful in many ways. David trusts Michael, mostly, and Michale trusts David, mostly. They respect one another and genuinely want to help the other succeed, because they are aligned in wanting David’s company to “succeed.”

Michael pushes David hard to hit funding milestones and projections fit the expectations of the Series A VCs that Michael is stoked to intro his favorite founder, David, to for their next financing. In engineering financial projections, Michael suggests that David should cut costs - he should ditch the hardware, move to a recurring revenue model, tweak his go-to-market strategy, be more ambitious in his targets…. He can still serve the same customer, but he has to do it in away that is palatable to other normal VCs.

Here we reach an inflection point.

Path A: David does what Michael suggests, but with a pit in his stomach and an increasing decrease in that semi-delusional confidence-in-product that is necessary to endure the startup founder roller coaster. David becomes less confident in himself, and more confident in Michael and other external voices. He does what they say, and he’ll raise that A round at the valuation range that delivers nice mark-ups that Michael can share with his LPs.

After the Series A, another 2 VC dudes (Mark* and Andrew*) join the board, and elect to replace Michael with a more “seasoned executive” CEO that they’ve selected. By the time Michael’s co reaches Series B, their product and mission is unrecognizable to him and his initial customer base. Maybe the new direction the company has chosen is successful, maybe not. The problem still hasn’t been solved for the farmers.

Path B: David says no, explaining that it won’t work to force SaaS metrics on his business, because it won’t serve his customers. Michael doesn’t agree, because Michael has experience and confidence. David grinds on through and tries to convert his company into a 🦪 overnight (which is super hard and painful when he’s been living on VC jet fuel for the past 12-18 months.) Michael writes off his investment in David’s company, but hopes that it will come back around. Their meeting cadence drops off, and David finds new close advisors. Michael fulfills his responsibilities as a Board Member, and David continues to cooperatively report to Michael’s fund. Michael continues to float options that would serve his fund’s goals - ideas that he thinks will best position David’s company for an acquisition, and David respectfully considers them, and maybe he even eventually acts on one of them. Michael doesn’t invest any more capital into David’s company, and he reallocates his focus and time towards other investments. Maybe David succeeds here in building a company that can grow off of its revenue, mixed with debt and aligned equity funding sources. Maybe not. This isn’t meant to be a high drama startup implosion - there’s far more nuance than that. This company is unlikely to be a 🦄 or a🐉 for Michael’s fund, because it’s valuation will never be huge, and Michael didn’t double down to buy enough of the company to enable the multiples that would be required for an exit to return the fund.

The scenarios that I’ve illustrated above are meant to increase mindfulness around taking founder-funder alignment - nothing else. Investors, especially at the early stage, are generally well-intended and are not trying to sabotage their investments (obviously - we’re trying to make $$$!) It’s not my intent to spook founders from taking investment. Rather, I’m trying to convey the fact that there are a lot of smart people controlling investment dollars who seem to suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect (they know a little bit, and therefore they think they know it all.) I’ve caught myself falling into this trap, personally (on the investor end) more than once. This can result in suboptimal outcomes.

2 - Lack of discpline around returns modeling

I think that there is, generally speaking, a lack of discipline about returns modeling, amongst early stage investors and startup founders. Let’s dig into it.

VC fund performance is measured by LPs (Limited Partners, aka fund investors) are measured on 3 basic metrics (warning, jargon):

DPI - Distribution to Paid In Capital, aka the ratio of dollars in:dollars out. In theory, VC funds are aiming to get at least a 3x DPI. In reality, this is rarely accomplished.

TVPI - Total Value to Paid in Capital, aka the ratio of dollars in:portfolio “paper” value. I personally think this metric gets way too much airtime, because paper value is fake. It’s like saying that the corn sitting in my families’ farms’ storage is worth todays’ basis price x quantity - that’s true, if we sell it today, but it might be totally wrong tomorrow.

IRR - Internal Rate of Return - this one factors in time, because the prevailing logic is that the longer it takes for an LP to get their money back, the higher the return (higher DPI) they should get.

In ag and climate investing, I find that many LPs actually don’t care as much about IRR. There are certainly many that too, and it does matter, but, if we want to keep it simple, DPI is the whole game. If an LP gives Michael-the-VC-from-above $1, he better give him back at least $1+y at some future date.

(Want to read more about the realities of what VC fund returns actually look like? Good post from Last Mile Ventures here.)

The other really important concept to understand is “dilution”- most companies that raise capital in exchange for equity do so over multiple “rounds” (colloquially: Pre-Seed, Seed, Series A,B,C,D…) Each round has its own set of terms, and shares increase in price with each round (theoretically/hopefully.) Each round results in dilution of the existing shareholders. Practically, this means that if Michael invested $1M at a $5M post-money valuation in David’s Seed round, then he bought 20% of the company’s shares. If there are no future funding rounds, he’ll still own 20% of those shares at “exit” (which is only a good outcome if David’s company exits at a valuation exceeding $5M, or if someone buys Michael’s shares for a higher share price than he paid for them. In Scenario 1A, though, there are future financings - at the Series A, B, etc, Michael’s initial investment (and David’s founder shares) continues to get diluted as other investors come in and as shares are rewarded to employees for incentivization. This gets complex, fast, and that’s exactly the point. Investors like Michael have to be thoughtful about how they calculate their return projections, particularly in the world of agtech, where exit valuations aren’t likely to be that high.

What’s needed for equity financing in agtech

Equity-based investment (buying shares in a company) is extremely useful as a tool to create alignment and incentive for high risk, early bets, and we need it in agtech. VC investors should be disciplined and more conservative than they are around setting current valuations and projecting future valuations. There’s a certain amount of startup puffery that is expected - VC investors expect bullsh*t hockey stick projections, and so they coach and encourage founders to play that game. I get it, and I’ve played it, but I hate it.

Ag-specific investors, especially those at the early stages, and founders should, I think, be more real with their respective investors with regards to timelines and truly addressable markets. They should, as transparently as possible, work together to build an ambitious but attainable plan that creates a win-win situation. High DPI can be achieved by investors on low-valuation exits in scenarios where the possibility of that low valuation exit was considered at the time of initial investment. If Michael and David from above had agreed that there was a real possibility that David’s company exited for only $20M by doing things David’s way, but that there was a really viable pathway to getting there without any additional funding rounds (dilution for Michael), then Michael could achieve a a 4x on his initial investment. That isn’t, though, in line with the portfolio strategy that a majority of funds take.

We also need more alternatives to equity investment in agtech, and I’ll get into that in later newsletters. If you have good ideas or direct experience here, reach out - I’d love to learn from and with you.

Over the past couple of weeks, these bits of content really stood out to me:

Alexis Estrada of Semillerio de Ideas was featured on a podcast interview with EFI’s Tip of the Iceberg. She spoke about putting farmworkers at the center of development and innovation in tech and the fact that agricultural work requires a deep set of specialized skills.

Seana Day wrote a great piece on the agtech gap+opportunity for services in AgFunder (plus she made a focused, differently formatted market map in part 2)